Respected fisher Al McGlashan says understanding, education key to sharing ETBF resources

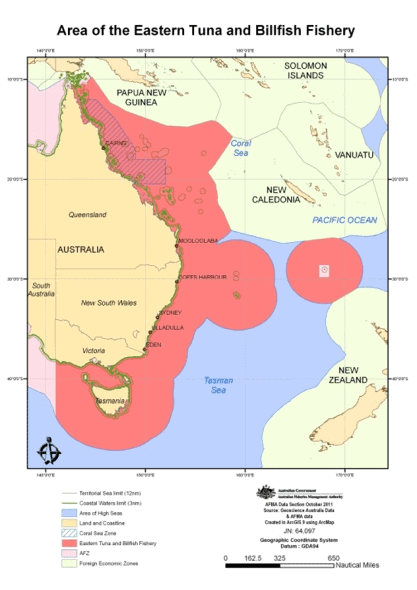

A respected fishing ambassador and media personality has praised examples of growing cooperation between commercial and recreational fishers in the Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery (ETBF), and called for further education and information sharing to better protect shared resources.

In a recent interview with Tuna Australia, Al McGlashan discussed his thoughts about the proposed Commonwealth Fisheries resource sharing framework.

The state of play

The framework is due in mid-2020 and the key aim is to ensure commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishers have fair access to commonwealth fisheries, like the ETBF.

Currently, recreational fishing for ETBF species is managed by Queensland, New South Wales, Victorian and Tasmanian state governments.

“All the states have different rules and regulations, but the fish don’t respect state borders, so it makes no sense,” said McGlashan.

Complicating this picture is that there are different rules for commercial and recreational fishers.

For instance, commercial fishers have to report every kilogram of fish they catch, as do game fishers when competing in a tournament and charter boats. Yet recreational fishers aren’t required to record their catch.

This gap in data collection creates challenges for state governments to effectively, and sustainably, manage the fishery.

Currently, state governments use surveys and tagging returns to collect catch information from the recreational sector.

“Recreational fishers should be able to report their catches, especially for more high-value species,” said McGlashan, “to help better manage them.”

It’s a privilege, not a right to fish these grounds, particularly when fishing for Southern Bluefin Tuna (SBT) and marlin.

McGlashan said the information being collected now is not enough and state governments “should be getting heaps more information.”

But he recognises that it will be a “tough sell” to get recreational fishers on board because “it’s been used against them in the past.”

“We have to promote record-keeping as something that’s done for the fish, and is actually for the fish to ensure sustainability, and not used against us by environmental groups.”

Sharing knowledge

McGlashan said that many recreational fishers are embracing a better understanding of how to process big fish.

For example, SBT doesn’t keep well—and will go brown—unless it is chilled down quickly upon capture.

“A decade ago, we were catching big fish and leaving them on the deck. We had no idea about cleaning and processing the fish, how to look after it or cook it,” he said.

“Commercial fishers process their fish immediately and thoroughly because the market demands premium product quality. But recreational fishers don’t always look after their catch as best they can.”

Recreational fisher and ambassador Al McGlashan.

McGlashan said understanding the SBT story was the inspiration behind the Tuna Champions movement, which encourages recreational fishers to use best fishing practices for SBT.

A big part of Tuna Champions is about informing recreational fishers on how to catch, handle, and keep SBT, ensuring the best possible product quality. They’re also shown how to tag and release these dynamic fish to minimise stress.

“However, we need more education to better understand processing the fish to the same level as commercial fishers,” says McGlashan.

“Tuna Champions is helping to drive positive change. For instance, I’ve seen a massive change in recreational fishers taking ice to sea. But it’s really only the beginning,” he said, acknowledging that Tuna Champion’s messaging should be extended to all ETBF species.

McGlashan describes Tuna Champions as a “great example” of working together and learning from each other, like commercial fishers teaching recreational fishers how to better look after their fish.

“We need more good news stories like this,” said McGlashan, whose Life on the Line documentary shares the true story of how fishing saved SBT, which was once destined for collapse.

“We always hear that everything is a disaster. But we need good stories of where we’re working together, so people say, ‘oh wow, how good is that!’.”

Yellowfin tuna. Photo by Al McGlashan.

‘Working together’

In the ETBF fishery, commercial and recreational fishers have been fishing the same resource for a long time.

On some occasions, resource access has created some tensions and conflicts, said McGlashan, largely due to misunderstandings between the groups.

“In the old days, recreational fishers and commercial fishers didn’t get along. There was a lack of understanding and some fishers accused commercial fishers of taking tonnes of fish, but it was simply a lack of understanding.

In reality, commercial fishers are highly regulated and not mucking around. They’re doing a good job at catching fish sustainably and are regulated to minimise their impact on the environment.

McGlashan said that both commercial and recreational fishers in the ETBF work together well in fishing ports. However, we need to improve the understanding across the entire fishery and work together to achieve a more favourable outcome for the whole fishery.

McGlashan, who’s been fishing recreationally around commercials vessels for decades, said it’s “very simple” to maintain a good relationship with commercial fishers.

“I’ve developed good relationships with skippers over the years and now we share information which helps everyone from finding fish to getting both sides closer together

Each side needs to share their story, so we understand each other better. That’s key.