‘What do statutory fishing rights mean?’ ask outraged fishers in the Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery

Decisions made by the Australian Government in the last couple of months have stripped AUD 30 million from the Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery (WTBF), and the zoning for the proposed Indian Ocean Territories Marine Park (IOMTP) will badly erode fishers’ statutory fishing rights to catch fish.

“We have seen the Australian Government supporting the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) to reduce tuna catches in the Indian Ocean, resulting in the total allowable catch of the WTBF being slashed by a whopping 60 percent,” said David Ellis, CEO, Tuna Australia.

“And now, the government plans to lock us out of highly important fishing areas from the fishery equal to the size of NSW with the zoning of the IOTMP without any structural adjustment.

“This is outrageous… So what do statutory fishing rights actually mean?”

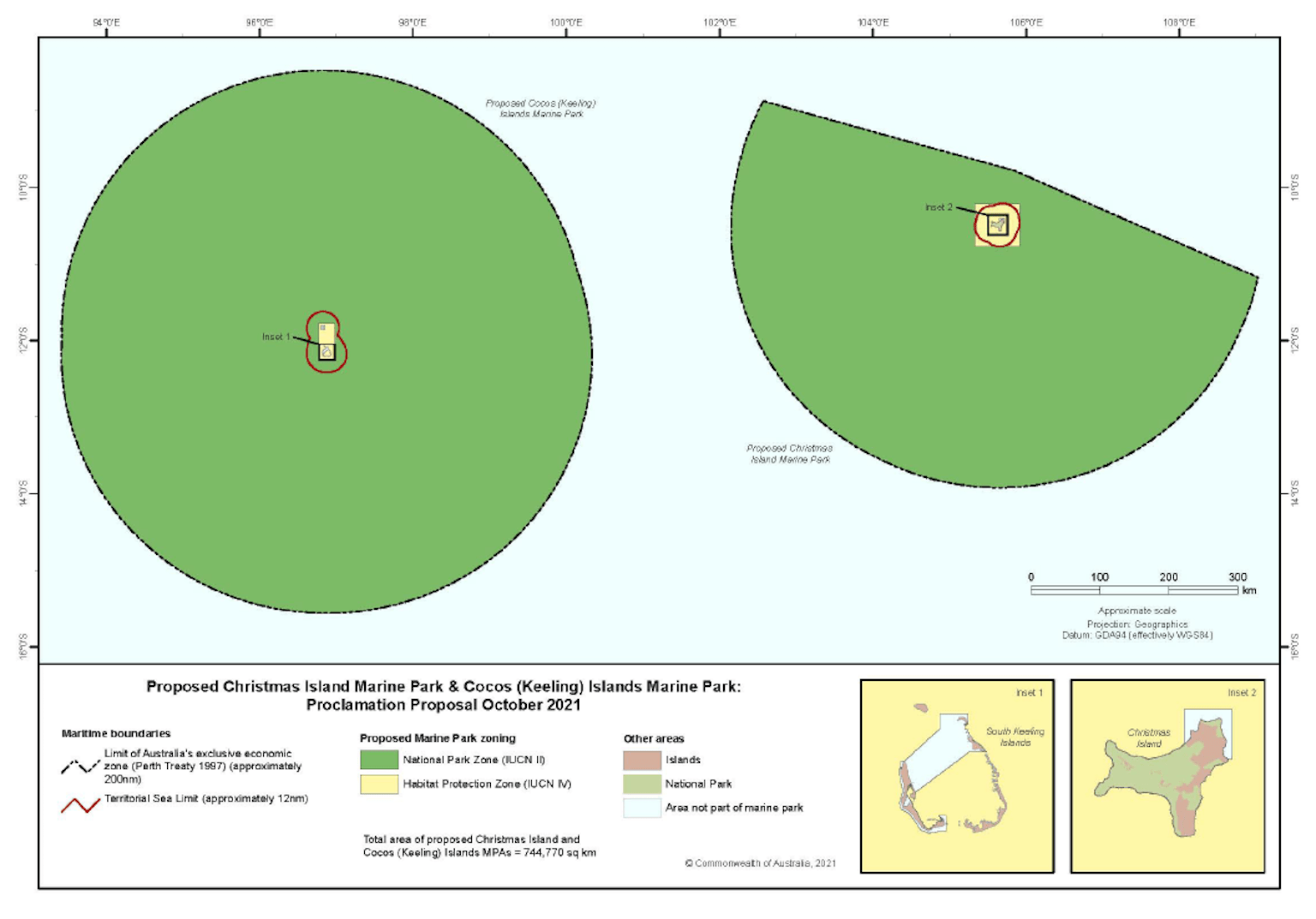

Under the proposal, the Australian Government intends to designate the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) surrounding the Cocos Islands and Christmas Islands, off the north-western coast of Western Australia, as an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Category II National Park (known as a ‘green zone’).

The proposed IOTMP zoning will see fishers excluded from very lucrative fishing areas.

“The proposed zoning makes no sense,” Bert Boschetti from Latitude Fisheries told Tuna Australia.

“We catch highly migratory fish that do not stay in these areas. Our gear does not interact or impact habitat such as coral reefs, seagrass, deep-water plains, seamounts and ridges highlighted in the proposal.

Our fishing method has absolutely no impact on the ocean floor, so why is there a need to take away our fishing areas?”

A simple solution would be for Parks Australia to classify the area as an IUCN Category IV Habitat Protection Zone, which would still offer protections for the sea floor from mining and other destructive activities, but still allow commercial fishing in the water column.

Tuna Australia and other fishing industry associations have advocated this position in various submissions to the consultation process.

Peverse outcomes

Compounding the impact of taking away fishing area, the quota, or total allowable catch (TAC), for yellowfin tuna has been reduced from 5000 to 2000 tonnes per year.

“This is a catastrophic quota reduction and equals an estimated AUD 30 million loss to WTBF fishers,” said Terry Romaro OAM of Ship Agencies Australia, based in Fremantle, Western Australia.

“Since the early 2000s, Australian fishers have traded statutory fishing rights based on a total YFT allocation of 5000 tonnes.

Considering over 400,000 tonnes of YFT are caught annually in the Indian Ocean, our tiny 5,000 tonnes is only a drop in the ocean!

“We have a fantastic opportunity to develop this fishery and create jobs in regional centres. But now, despite fishers following world-best practices for sustainable fishing, our quota has been cut and the rug has been pulled out from underneath investors,” said Romaro, who’s been involved in the tuna longline fishery for 54 years.

“We have implored our government to insist that all foreign tuna vessels in the IOTC follow the same rules our fishers follow. This should be a minimum requirement so that all catches are accurately recorded and interactions with protected and endangered bycatch species are minimised.

“These operating conditions should be standardised across the Indian Ocean tuna fishery before we ever consider any cut to our quota allocation.”

'Confused and mystified'

The IOTC is the intergovernmental organization responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species in the Indian Ocean.

The decision to cut the WTBF yellowfin tuna quota was made during the Technical Committee on Allocation Criteria meeting on 28 June to 1 July 2021.

“The IOTC convened the meeting to address overfishing of Yellowfin tuna by member countries operating on the high seas, predominantly in the Western part of the fishery,” said Ellis.

“The IOTC failed to recognise that the WTBF is being managed using a precautionary approach, which emphasizes conservation and environmental considerations.”

Fishers in the WTBF have been conserving yellowfin tuna stocks by leaving them in the water to let them multiply for long-term sustainability.

Unfortunately, the IOTC made the quota decision based on recent catch history, which the WTBF does not have, explained Boschetti, who attended the IOTC meeting.

“As a result, industrial fishing nations that have been pillaging the Indian Ocean will continue to do so, while those that have not contributed to the overfished status of Yellowfin tuna, such as Australia, have taken a massive cut to their quota.

The new measure sees Australia subsidising distant water fishing fleets to continue catching fish unsustainably.”

The quota cut decision has “confused and mystified” commercial fishers in the WTBF like Kim Newbold of Hawkness Pty Ltd, who also attended the IOTC meeting.

“The government implemented statutory fishing rights in the WTBF and now fishers, through no fault of their own, have had fish taken away and are going to lose another 744,000 square kilometres of fishing area without any compensation or structural adjustment.

“Industry should not have to carry the cost in time, resources or money to address issues like these.

"Why is Australia not trying to develop or support the development of a real national fishing presence in the Indian Ocean?" asked Newbold.

“The Australian Government has an aspirational goal of supporting agriculture industries to achieve AUD 100 billion in primary production by 2030. But, at the same time, the government is actively working against our food-producing sector by systematically ignoring and blocking our efforts to develop the fishery in a cost-effective and community-conscious manner.

Australia as a nation and its fishing industry is being sold down the river."